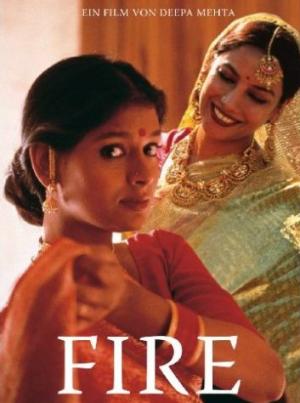

This bold movie tells the story of two women who are married to brothers in a joint family. Through shared loneliness, they soon start a secret affair within the household. It is written and directed by Deepa Mehta, and stars the young and pretty Nadita Das and the quietly beautiful Shabana Azmi who play their roles quite convincingly. The music seems to have been taken from A.R.Rahman’s work on the movie Bombay. There are mysterious and slow interludes where a child Radha is being taught by her mother how to see the ocean without seeing it. The story begins three days after the Jatin, the younger brother, marries an enthusiastic, inquisitive and open-minded Sita.

Jatin continues his affair with his Chinese girlfriend, Julie, and is soon found out by Sita. Though initially hurt, she soon accepts this state of affairs. As the story unfolds we find out that Jatin did indeed ask Julie to marry him, and his family was even willing to accept her though she wasn’t Indian. But she refused to marry him because she didn’t want to get tied down in a marriage, let alone in a joint family system full of duties and ‘baby manufacturing’. He is in love with her and seems quite blinded, to such an extent that he sees her plan to move to Hong Kong as ‘ambition’ rather than a reason to believe she may be bored of him and want to start anew. She has total power over him by simply not committing completely. Puppeteer. Her family, insults India in front of Jatin during dinner one night saying there is no place for minorities here and that it has just become developed and therefore gotten an ego of its own though it is no where as good as Australia or Canada. Jatin takes these insults lying down instead of defending his country to those who behave like outsiders. It is often a point a great criticism that the people who insult India the most are Indians themselves. I wonder why a country like ours doesn’t have the pride it deserves. The fact is, minorities get a lot more attention simply because they are minorities. The votes controlled by them make or break coalition governments (which seem to have become the norm in our great democracy). Minority religious groups even get government funding for their pilgrimages whereas the run-of-the-mill Hindu receives no such benefits. The quota system too; oh, let’s not get started on that now. Jatin manages a diplomatic understatement; “Yes, India is quite complex.”

The other couple in the house have not had sex in thirteen years. When the older brother Ashok found out that his wife Radha could not bear children, he took a vow of celibacy because he believes that a sexual relationship serves only to produce children. This view shocks me because it sounds more Christian-purist to me than Hindu. Where does Ashok think the Kama Sutra came from, I wonder. We were once a tradition that embraced our sexuality. We have sculptures in our temples that portray it. It is accepted as part of nature and even seen by some, as another means to explore one’s spiritual connections with one’s other half (Shiva-Parvathi). I’m quite sure from what I’ve read of the Samsaric and Mokshik paths we choose in life, that a man has a choice before marriage to take up Sanyas (renunciation of all material desire and possessions and live a simple austere life). But a girl’s father tells him of his Samsaric duty to society and offers him his daughter’s hand in marriage. The man is then convinced that he can pursue god within a social life as well (This little procedure is now a little skit played out just before the primary wedding ceremony. It is called Kaashi Yatra in south Indian weddings.) So once he has chosen a Samsaric life and married, it is wrong for him to renounce his worldly pleasures. And if he feels the spiritual pull that much, he must leave altogether and live in a forest. So what Ashok decides to do is wrong according to Hinduism itself. Quite ironic, I’d say.

The other two characters are Biji, the old woman who cannot move or speak but rings a bell for attention, and Mundu, the servant who ignores Biji’s protests and watches adult videos in front of her. They are disapproving spectators.

Radha and Sita start spending more time with each other, share their loneliness and find that they are attracted to each other. Or perhaps they turn to each other for comfort, company and for sexual satisfaction. I would say that the naming of these two characters is what we call in Tamil ‘adhigaprasangithanam’- roughly meaning unnecessarily provocative.

For those who don’t know, Sita is Rama’s ever so faithful wife in an epic called Ramayanam which is considered by many Hindus to be of religious importance. You will also notice that the Agnipariksha (fire test) is played out several times during the movie as a background religious activity or part of the Ramayan movie (in Hindi). This episode in Ramayana tests the purity of Sita after she was abducted by Ravana (the bad guy). Rama claims to trust her but his duty as king, to his suspicious subjects, is to ask her to stand in the holy fire. If she was indeed faithful to him, she would not be hurt but if she was, she would burn alive. Of course, she passes the test in the epic, (as Radha seems to in the end of the movie.) But Sita also leaves Rama after that, saying that since she was born of the Earth-goddess, her element takes offense to the fire-test. The repeated Ramayana background also gives an impression that it is central to Hinduism. There are plenty of other gods, philosophies and subbeliefs under the umbrella of Hinduism (even atheism!). Nevertheless, this background and Sita being the younger woman’s name in the movie is supposed to draw some contrast between what is expected of a wife and what a modern woman actually does. To make it worse, Radha is the name of Krishna’s beloved. Both Rama and Krishna are gods- avatars of Vishnu. Which makes such naming as close to ‘sacrilege’ as possible within the broadness of Hinduism. It is no wonder there were objections to this movie when it was released. Those who are particularly fond of Rama-Sita or Radha-Krishna would surely be offended.

I think the coupling of Radha and Sita also touches a nerve with real lesbians because lesbians don’t choose women over men as a second option, or as an alternative way to meet their sexual needs. They like women, not men.

This movie also exposes the blatant patriarchy in the family system. Ashok is only mildly reproachful of Jitin continuing his affair but boils right over when he discovers their wives’ infidelity. The women take care of the elderly, serve the food, wait up for their husbands, perform prayers and fast for their husbands’ long lives, etc. while the husbands neglect their wives by demanding sex without any love, telling her that a baby will ‘keep her occupied and happy’, and having an open affair, or using the wife as a measure of one’s shaky-religious self-control for thirteen miserable years. The women are expected to obey and fulfil the wishes of their husbands (except sexual, thankfully), never talk back yet they receive no respect for their minds nor gratitude for how much they do for them. So was I cheering when Sita slapped Jatin back instead of cowering and crying like in all the other movies of the 1990s? Hell, yeah!

In fact, I enjoyed the whole part where Jatin realises Sita is cooler than she looks and hesitates before leaving the house for Julie again. Quite possibly that fight, and her continued indifference towards him made him fall for her. There was simply no time left in the movie to spell it out.

Fire was ahead of its time; taking on controversial topics like lesbianism, and feminism in equally controversial contexts of (a narrowly defined) religious and sexual setting. It brushes aside censorship rules about lip to lip kissing and nudity. What I found most refreshing was how vividly it contrasts with other movies of its times in portraying women. I am quite disgusted by the spinelessness that women characters were given during that time. Anything a man did was acceptable, even physical violence, because he was the husband. A woman had no right to expect or ask for more than what he was willing to give. She would quietly cry but never speak out. This was portrayed as the qualities of a good wife! The namesakes of two goddesses/mythical women are shown as strong enough to leave their unsatisfactory, loveless marriages for something they believe and commit to. While both husbands are left in shock and slimy situations, these women break out of the moulds of their ‘support-role’ namesakes of the myths and become the victorious heroes in the spotlight.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0116308/